Scottish Horror

Whiles glowrin round wi' prudent cares,

Lest bogles catch him unawares.

Kirk-Alloway was drawing nigh,

Whare ghaists and houlets nightly cry.

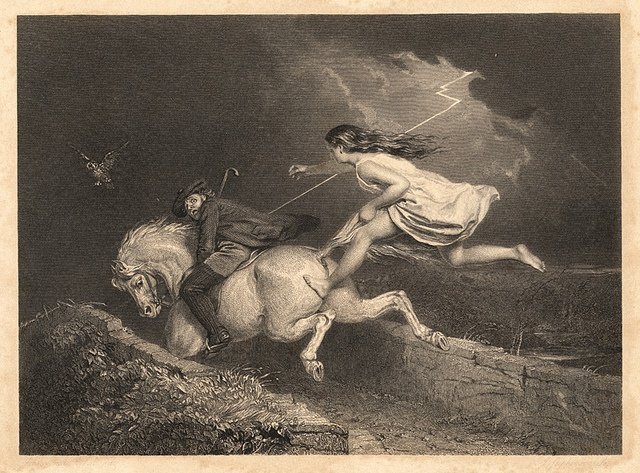

The poem, Tam O’Shanter by Robert Burns may be one of the earliest examples of horror in Scottish popular culture. It tells the tale of hapless bevvie loving Tam, whom, after a hearty few days on the razz in the town of Ayr, stumbles across a horrifying, supernatural scene at “Alloway’s Auld Haunted Kirk”.

Witches and warlocks dance with abandon to a skirl given by a bagpipe playing Satan, or Auld Nick as Burns calls him, among open coffins and weapons used in local murders. Tam sits atop his trusty horse, Meg (A better never lifted leg) watching the dancing witches gradually remove their clothing. Suitably pissed up and doubtlessly horny after spending the evening flirting with the pub landlord’s wife, Tam fails to contain himself, shouting out:

“Weel done, cutty sark!”

The party ruined (Not the last time a sexy party will be spoiled by a boisterous drunken Scotsman) the witches chase Tam who takes off like the clappers on the back of trusty Meg. The instincts of self-preservation cut through the effects of his days’ long session, when he remembers the denizens of hell can’t cross running water. He and Meg just make it across the Brig O Doon, but not before the poor horse’s tail is pulled off by one of the pursuing witches.

I was introduced to the poem at Primary School when we were being taught about Burns in the mid-1980s. I remember being horrified and fascinated by the vivid descriptions of the occupants of the open coffins and frantic witches in short skirts. I was still young enough to be legitimately afraid of the dark and my mind was well and truly open to the possibilities of the sinister and supernatural.

When it was published, the poem was considered a tongue in cheek warning about the dangers of boozing (Ironic considering the author’s reputed love of a dram) and a warning to Carrick Farmers not to stay late in the taverns of Ayr on market day. I suspect it’s an example of Burns having fun with his craft and exploiting the convention and superstitions of his readers.

The history of Scotland is often grizzly and horrifying, vibrating with legend and folklore which sit between real-life horror and the supernatural. As such, filmmakers over the years have turned to this rich, blood-soaked history for inspiration.

The legend of Sawney Bean is somewhat ambiguous, but the popular version of events puts the legendary killer and cannibal on the west coast of Scotland in the 16th Century.

He’s said to have lived in a coastal cave on Bennane Head, near Girvan with his wife and incestuous family, ambushing and murdering travellers on the road at night, before taking their bodies back to the cave to be devoured.

Wes Craven, director of horror classics such as the franchise starting Nightmare on Elm Street, Scream 1-4 and notorious “Video Nasty” revenge thriller, The Last House on the Left would take inspiration from the murderous Bean clan for his 1977 film, The Hills Have Eyes.

In the movie, an inbred, cannibalistic family ambush and slaughter hapless travellers in the Nevada desert. During the course of events, members of the luckless Carter family are shot, crucified and raped by the depraved family. Even by modern standards, the movie is graphic and harrowing. It was refused classification in the UK “…due to considerable violence and cruelty…”. You can probably pick it up on DVD in the horror section in HMV now though. Proceed with caution, it’s not for the sensitive.

Sawney – Flesh of Man, or Lord of Darkness in some countries, has fun with the contention that one member of the Bean clan survived the gruesome justice said to have been visited upon them by the local authorities and began a new dynasty of cannibalistic bampots. We meet their descendants in modern day (2012) Scotland, living in Highland caves and venturing into the big city for victims. Swally favourite David Hayman plays the titular character and by all accounts both literally and figuratively chews the scenery. See what we think of the film on a future episode of the podcast.

The legend of Bean and his bloodthirsty family has been analysed and debated for well over 200 years. His very existence remains questionable. Edinburgh murderers Burke and Hare, however, are a different case altogether. They were very real, and we have the bones to prove it.

In the University of Edinburgh’s Anatomical Museum, in the Surgeon’s Hall, there’s a glass cabinet displaying the complete skeleton of one William Burke. Burke and his cohort, William Hare discovered there was money to be made by selling the bodies of the recently deceased to the anatomists of 19th Century Edinburgh.

Hare’s elderly lodger, Donald had died owing his landlord four pounds in back rent. A local carpenter provided a coffin for poor Donald. When his work was complete, Burke and Hare removed the body and filled the coffin with bark. Donald was placed under a bed until after dark, whereafter the pair took him to Edinburgh University and sold him to Doctor Robert Knox to be used in anatomy lectures for his students.

Over the next ten months, Burke and Hare would go on to murder sixteen people and sell their bodies to Knox for around ten pounds each (Approximately a thousand pounds in today’s money) before their arrest. Hare would get away with his crimes, but Burke was convicted of just one of the murders, which was enough to see him hanged. The judge himself ordered that’s Burke’s body was to be given for public dissection and his skeleton preserved “…in remembrance of your atrocious crimes…”.

One of the first artists to draw inspiration from the crimes of Burke and Hare, was celebrated Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson. His 1884 short story, The Body Snatcher, was first published in the Pall Mall Gazette and tells the tale of two trainee surgeons, studying under an eminent surgeon called Doctor K. One of the students’ duties is to pay the mysterious men that bring the fresh bodies for dissection in Doctor K’s anatomy classes. Soon one suspects the other of committing murder to ensure a continual cadaver supply.

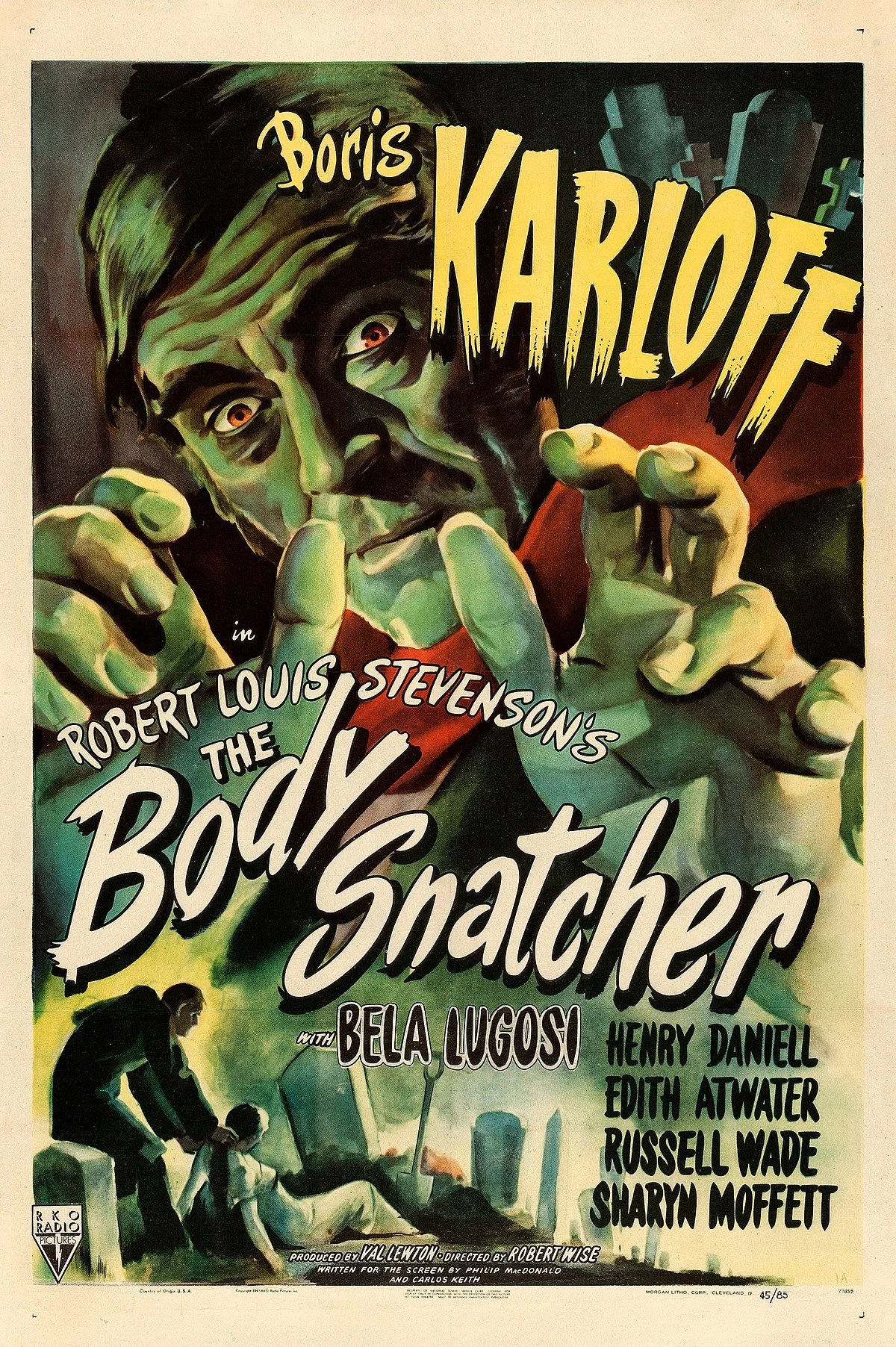

The Body Snatcher was loosely adapted into a film of the same name in 1945. It was directed by Robert Wise, who would go on to direct spooky classic, The Haunting and the first film adaption of West Side Story. It also starred OG horror superstars, Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi. The producer was Val Lewton, the horror supremo behind low budget classics such as Cat People (1942), I Walked with a Zombie (1943) and The Leopard Man (1943).

One of the most famous and, in my humble opinion, the best interpretation of the story of Burke and Hare is 1960’s The Flesh and the Fiends. Directed by Hammer director John Gilling and starring Peter Cushing as Doctor Knox, famed character actor Donald Pleasance, Billie Whitelaw and George Rose, TFATF (Or Mania, if you’re in the US) is a bleak, atmospheric telling of the crimes, full of couthy characters, bad teeth and dodgy Scottish accents.

It performed poorly at the time of release but over the years has been subject to a more positive appraisal by critics. Directors Quentin Tarantino and Edgar Wright are both fans of the movie and you can hear them discuss it on a rather good episode of the Empire Magazine podcast. You can find TFATF on YouTube. I’ve added a link to the picture above using my amazing website building skills Check it out and let us know what you thought of it.

On the Swally, we have an annual October tradition of choosing a scary film or television show to discuss on the month’s episodes. We began this tradition in October 2021 (Episode 33) with director Neil Marshall’s debut film, Dog Soldiers.

Dog Soldiers see’s Kevin McKidd and Sean Pertwee’s gristly squaddies facing off against a family of werewolves in the Scottish Highlands. If you haven’t seen the film, we can heartily recommend it. It’s a great mix of horror, drama and pathos, thanks in no small part to brilliant performances from McKidd and Pertwee. I wouldn’t say it subverts the werewolf concept much, but rather leans into the classic troupes to great effect.

For one of our Halloween episodes this year, we covered a rather less well known spooky, Scottish production, 1989’s Govan Ghost Story. Written by Bryan Elsey as part of the BBC’s anthology series “The Play on One”, GGS tells the story of widower Jock, played by the excellent Tom Watson. A former ship wright, Jock is estranged from his adult daughter and haunted by more than just his memories of the famous 1971 Upper Clyde Shipyard “Work In”.

Watson is superb as the cantankerous Jock, struggling to mend his relationship with his daughter and disturbed by the creepy occurrences in the empty flat next door. In less skilled hands, GGS could have been a somewhat contrived, by the numbers spooky tale. But Elsey’s writing, combined with the performances of the cast elevate it to something very special. It’s also available to watch on YouTube and once again, thanks to my formidable skills, a cheeky click on the picture here will take you straight to it.

Arguably, the most famous horror film with Scottish connections is 1973’s The Wicker Man. Conceived as an antithesis to the popular Hammer films of the time, director Robin Hardy and screenwriter Anthony Shaffer set out to make an articulate and scary film, in a modern setting depicting a confrontation between a devout Christian and an isolated Pagan community. The Isle of Skye, Stranraer and Plockton are just three of the beautiful Scottish locations utilised by the production to represent the remote island of Summerisle.

Edward Woodward, sporting a superb Scottish accent by the way, plays virginal Sergeant Howie, dispatched to Summerisle to investigate the disappearance of a young girl. Hammer stalwart Christopher Lee, keen to break away from playing vampires and monsters and move his career in a new direction, signed on as charming community leader Lord Summerisle. Despite appearing in nearly 300 movies in his long and storied career, Lee considered The Wicker Man to be his best film.

Rising star Britt Ekland plays Willow, the pub landlord’s seductive daughter. The script called for her to take her clothes off, but Ekland discovered during filming that she was three months pregnant, so body-doubles were brought in for the scenes where Willow attempts to lure Howie to her bedroom by singing a song and performing a sexy dance through the shared wall.

Ingrid Pitt, another Hammer Studios veteran plays the island librarian and look out for Govan’s own Jamesie and Ella Cotter, Tony Roper and Barbera Rafferty in small roles. Although, you’ll have to watch the extended version to see Roper do his turn as “Postman”.

The Wicker Man will celebrate fifty years in 2023 and the film still packs a serious punch. Genuinely creepy and unsettling with fantastic performances from the cast, especially Woodward and Lee, it still has the power to shock. The final scene depicting Sergeant Howie, locked in the blazing Wicker Man as a sacrifice to the islander’s Pagan gods, will stay with the audience long after the credits have rolled.

Look out for reviews of more recent Scottish horror titles in upcoming episodes of the podcast. There have been a lot of releases over the last few years which I came across while researching this essay. In 2022 we covered horror comedy Get Duked and the Straw Dogs-esque White Settlers, but have you heard of Dark Highlands from 2018? How about 2019’s Death of a Vlogger? One I’m particularly intrigued to see is 2013’s Lord of Tears and I’m not sure I’ll be waiting for October to pick it…

Let us know your favourite scary Scottish films on email. There’s a button at the top of the page. We won’t share your details with brazen soulless marketing companies, but we will give you a mention on the podcast. Which is always nice. Feel free to correct any of the above facts too. I won’t take it personally.

But whatever you do, don’t stay late boozing in the town of Ayr on market day, lest you go the same way as poor old Meg’s tail.

Whene'er to drink you are inclin'd,

Or cutty-sarks run in your mind,

Think, ye may buy the joys o'er dear,

Remember Tam O' Shanter's mear.